I recently found out about the Canon EOS ‘M’. It’s a very lightweight, cheap (~$350) Canon camera that can accept all the standard lenses (with an adaptor). I was about to write ‘DSLR’ there instead of camera, but technically it isn’t as the EOS M doesn’t have a viewfinder, mirror, flash or any of those other fripperies that bump up the price and size of cameras.

I’ve been wanting a full spectrum camera for ages, but I didn’t want to risk performing surgery on my ‘proper’ DSLR to get one. But for $350, I’m just comfortable with my tinkering skills to risk the attempt.

What exactly is a full spectrum camera? Well, a standard CCD or CMOS sensor is actually sensitive to more than just ordinary visible light. Camera manufactures well know this and try to avoid it, since to their customers it’s a nuisance if their photos don’t match what their eyes see. Even worse, since all lenses have some element of chromatic abberation, and don’t focus IR or UV light as well as they focus visible light, the extra light can often just show up as a ‘haziness’ rather than a clear image.

Camera designers use two ways of combating this problem.

- ‘Hot mirror‘ — This filter blocks infrared from reaching the sensor. It’s located inside the camera, and is sandwiched just above the sensor chip.

- ‘UV filter‘ — This blocks the UV in sunlight from creating unexpected effects on the image. It’s usually an optional extra that’s placed on the end of the lens. They’re so ubiquitous and cheap that many photographers recommend leaving one on your lens all the time, so that any scratches damage a $20 filter rather than a $400 lens.

I wanted to remove the hot mirror and leave myself with a camera that’s suitable for infrared, UV and also general astrophotography.

This website was an absolute godsend for info on opening up the EOS M:

http://www.scotttorborg.com/canon-eos-m-teardown

Here’s the camera, 3 hours old and already having terrible things done to it:

I laid everything out on this magnetic whiteboard (picked up from here). It’s a beautiful way to do it, and allows you to systematically work through the disassembly process.

The camera is starting to look decidedly unhealthy now:

An hour in and the first trouble emerges. I need a torx screwdriver that’s not in my home kit, so I have to pack up and change venue.

The optical assembly is held onto the main frame by those 3 torx screws, which oppose 3 springs. This allows canon to dial in the flatness of the sensor relative to the frame, and ensure the entire sensor is in focus. Sadly that meant that in order to get to the sensor, I have to destroy the calibration:

I didn’t take any photos of the filter, sorry, but I eventually got it removed succesfully and started putting the camera back together:

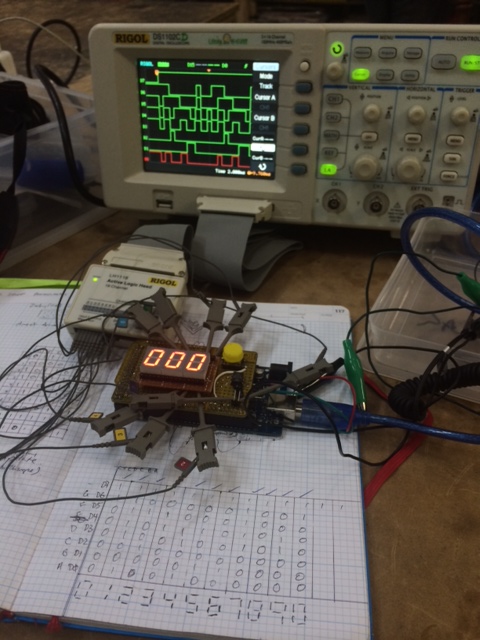

It was starting to look good, but I’d changed around a lot of cables and parts, and I needed to test the camera still worked. I slipped in the SD card and battery, and installed the EF adaptor and my stock lens. Powering up revealed the screen didn’t work, but the camera seemed to respond otherwise (trying to autofocus, etc). I turned it off, carefully took the back off again to reseat both cables to the LCD, and put the case on again.

This time the screen came on beautifully and everything seemed to work fine. Right up until I hit the shutter button, and the camera made a funny noise and went blank. Crap.

I popped the battery out and in again, and tried a couple more times. Seemed like the screen and all the buttons were working, along with autofocus and almost every other feature, but whenever the trigger was pressed it shut down. Hmm… how to troubleshoot. OK, these symptoms could mean it’s a fault in one or more of:

- the SD card,

- the trigger button assembly,

- the sensor, or

- the shutter.

How to disentangle these options? Aha! I put the camera to movie mode and hit record. It worked beautifully and I was able to record and play pictures with no problems. That gave a clean bill of health to everything on the list except the shutter mechanism.

Now I had my hint as to where the problem was. I carefully opened the case again and inspected the cables, but everything seemed to be seated correctly. Using a fine tip screwdriver, I carefully advanced the gears I could see on the shutter motor until I heard it click, then moved it around a bit to check it wasn’t getting jammed.

When I reassembled and powered up next, everything was working fine and I was able to take a couple of shots:

First light from the modified camera

After stress testing the camera in a bunch of different modes, shaking it and ensuring that I hadn’t left anything loose, I was pretty satisfied that my evening’s work was done correctly.

Now the sad thing about IR modding your camera at night is that everything looks pretty much the same.

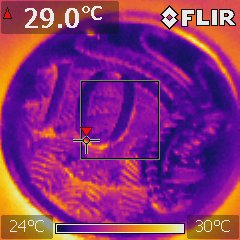

However the next day I managed to have some fun grabbing these pics. These were taken with the modified camera, but with an infrared-only filter added to stop visible light from entering:

Almost all the foliage seems white. This is know as the Wood Effect (after Robert W. Wood, not cellulose)

Here’s what the river looks like when I don’t put the 850nm IR only filter on the camera. Note the pinkish tinge of the sky, which is the exact effect that the IR-blocking filter I removed was there to stop:

So, for $350 and an evening’s tinkering, I managed to get a very flexible sensor that I should be able to use for lots of projects in the future. I’m pretty happy with the outcome.